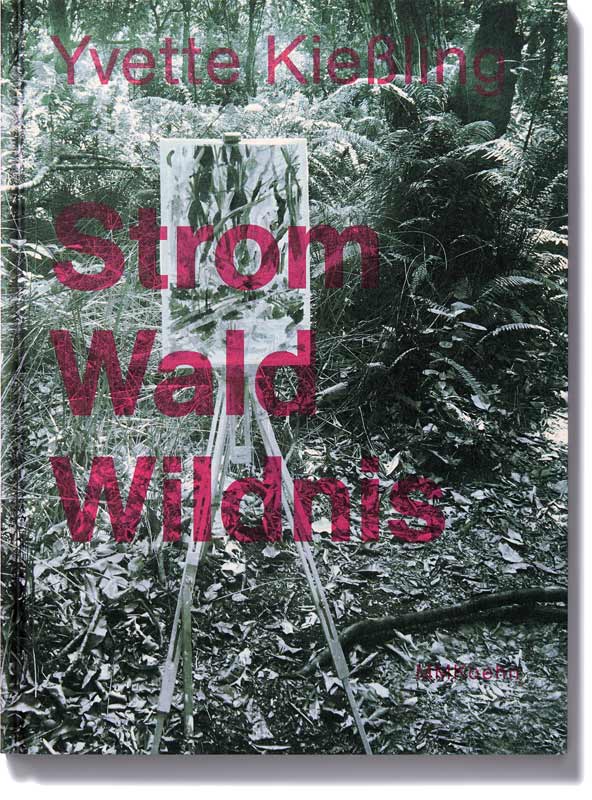

Scenic spheres, pictorially captured.

Observations on Yvette Kießling’s painting en plein air in the moors by Bremervörde.

Moors are inhospitable places, their nature particularly untouched—the jungles of the sweeping heaths. They consist of millennia-old plant particles and form landscapes of unmatchable suspense. Such places fascinate the Leipzig painter Yvette Kießling, who seeks out, for her pictures, those landscapes in which she senses a special aura. In her oil paintings, she develops equivalencies for what she experiences in nature. Her aim is to capture the tensions and harmonies she senses in a place and to translate them into her pictorial language.

Over the past years, the painter has discovered her landscapes both along European streams — especially the Elbe and the Rhine — and in far-flung areas like the tropical regions of the Usambara Mountains in Tanzania. After extended stays in such places, the moorlands around Lower Saxony’s Bremervörde now make up her newest area of study. Unlike the thick, noisy tropical landscapes, the moors, with their quiet expanses, appear downright hostile. Their great age and the “dense energy” she perceives lend them a special appeal.

Yvette Kießling paints en plein air: face to face with nature, never mind the wind or weather. All works presented in this catalogue were created under open skies. For the impression of a landscape that interests the painter is so multifaceted that it cannot be adequately captured in photographic or similar reproductions. These impressions transcend the visual appearance and include both knowledge about the site — here particularly the millennia-old history of the plants condensing in the peat — and the lived experience — the daylight and its transformations—as well as her own constitution and inner state at the moment of her natural encounter. Of course, no picture can directly capture either the cold that creeps below one’s clothes on a rainy autumn day, or the cranes that descend in flocks upon the moor, commanding attention from time to time with their loud calls — but these are all aspects of the painter’s impression of the landscape that she seeks to express in her paintings. Yvette Kießling is uninterested in reproducing a scenic situation as she visually perceives it. She is not fixated on documenting each individual element’s concrete number and location, or its specific hue. Rather, she translates what she sees in the manner in which the image demands. The painter compares the process of translating the discovered scenic sphere into the pictorial medium to freestyle musical improvisation. With an ingenious system of revisionary colour applications, she develops her images successively. Her particular handling of oil paints allows her to capture the process of experience: After laying out the image’s structure, she adds its pieces—the plants, clouds, sky, shadow surfaces etc.— step by step, yet always permits herself to remove them again, scratching them out or wiping them off with turpentine. In this continual process of creating and taking away, Yvette Kießling subjects herself to the landscape and presses onwards until she recognises her impression of the site in the picture.

Part of her experimentally playful painting process is her treatment of an imprimatura, a colourful background increasingly found in Yvette Kießling’s pictures. Responding to these at times vibrant and loud shades (magenta, orange, violet or ultramarine) poses a particular challenge in the painting process. The initially selected musical backdrop —to stick with our image of musical improvisation — can be described as the developing painting’s tone. In selecting the prepared, colourfully composed pictorial medium, the artist relies on her spontaneous judgment while regarding the landscape and mood of the day. It is this fearlessness and spontaneity in Kießling’s painting — expressed also in her colour choices, quick strokes and strong interest in the oil paint’s substance — that produces the strong dynamic inherent to her paintings. Her rapid painting method is reflected in various open structures. The pictures often peter out towards their fronts or sides, leaving the backdrop visible on the edges and condensing the image towards its centre. This creates the exciting compositions and unique dynamic that characterise Kießling’s pictorial interpretations of landscapes. The painter developed the intense vibrancy of her pictures during her residencies in Tanzania, where capturing the lush tropical vegetation called for strong colours. She has since retained her willingness to wield strong hues, and now increasingly applies them to those pictures she bases on European landscapes as well. On Bremervörde’s moors, she has thus created paintings that are fascinating expressions of the quiet of the wide moorlands, with its air of loneliness and calm, in startling tones and unexpected dynamic energy.

Yvette Kießling often returns to the places that she has already explored through painting once before. In the past years, this has produced an array of scenic spaces that serve as the objects of her visual world: the Elbe’s source and estuary, the Usambara Mountains. Hopefully, the moor, too, will play a lasting role in the painter’s oeuvre and develop into a site of long-term artistic examination — one from which paintings may emerge that lend onlookers a new understanding of this extraordinary natural sphere.

Benjamin Dörr (Berlin)

Dr. Benjamin Dörr is an art researcher and art historian, a lecturer at the Fachhochschule Potsdam and a freelance publicist. He wrote his dissertation on the middleclass garden art of the Biedermeier era. By empathising with places that used to be parks but are frequently nothing more than overgrown, wild natural environments today, he feels a kinship with the painter Yvette Kießling’s methodology.

Elbe Quelle Source

Drawing from the Source

Yvette has found her site of power. Since 2014, she has been occupying herself with the Elbe’s source, Labská louka (Czech for ‘Elbe meadow’), located almost 1400 meters up near the town of Špindleruv Mlýn (Spindler’s Mill) in the highlands of the Czech Republic’s Riesengebirge.

The artist created the large-sized painting Elbequell (‘Source of the Elbe’, 170 x 190 cm, oil on canvas on wood) in 2016, her glazed brush strokes capturing a landscape’s expanses in delicate shades. A plane is visible in the foreground, while the suggestion of mountains melts into blue before a cream-coloured sky behind. This plane – the Elbe’s meadow, from which the river springs – is rendered in incarnate, a pale flesh tone, structured with olive green and dark accents that lead towards the oval pools of water, brightened with white. The use of red, pink and white, jointly forming a further, more intense flesh tone, centrally divides and draws this plane in from the horizon: What results is a painterly pull towards the dark zone and to the overflowing surfaces of water. The painting’s aura is sensual, corporeal. Its title with its missing final ‘e’ leaves its further progression open – like the pool that reaches the picture’s edge. Elbequell…

The spring, la source, the origin, l’origine du monde – starting with Christian iconography and its springs and wells open for symbolic interpretation to the 19th century with works like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s La Source (1820–1856) or Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde (1866) and La Source (1868) – is a well-known theme in occidental art history. Religious symbolism casts the source as the miracle of creation, salvation and (eternal) life. In the 19th century, works on this theme are frequently nude depictions of naiads, the spring’s nymphs, by water. Aside from their significance for fertility and sexuality, these female figures can also be interpreted in relation to questions of artistic creation and inspiration – which into the 20th century seem to have been preserved for man alone. Female models and muses served as the male artist’s inspiration, they were not to act as creators themselves.

Kießling, a 21st-century artist, frees herself from such mythological and figural supports, instead drawing directly from her scenic motif. Since the first painting described above, she has produced diptychs that also deal with the Elbe’s source. Using as her starting point a lithograph of two single pages (82 x 60 cm each) she had created for Hamburg’s Griffelkunst Society 2016, she developed over-paintings with oil paint and oil pens on the coloured variants left over from the printing process, previously concealed on Alu-dibond. The template for the original lithograph was created on paper in situ – the artist seeks this place out multiple times per year and works en plein air. The Elbe’s source is a place in which she can work slowly and calmly, where intense seeing and feeling are possible. It is vital that she feel the energies and real scenery physically as well – photographs cannot serve as substitutes. In muted tones of mostly brown, green and red, the original lithograph depicts the Elbe’s meadow in the foreground, a rockier zone with coniferous trees (firs and mountain pines) in the middle ground and a sloping mountain in the background left, the Violík (Violet Rock).

The 15 over-paintings Elbwiese, Labská louka, she has created in rapid succession since 2017 are based on this multi-toned ink lithograph. Some let much shimmer through, some less, and above all go much further in regards to content. Previously, Yvette Kießling’s work was strongly influenced by her engagement with what she found in a specific place: She worked in, with and about a specific location, such as the Jozani Forest in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Something different is now happening in these works, something new: The Elbe’s meadow, drawn from memory and personally captured on the undercoat, serves as the sounding board, as an agitable neuroplexus for the over-painting. Like the Elbe flows from the Elbe’s meadow, the over-painting flows from the lithograph’s base. Yet not by itself – an echo requires an input. That input, in this case, is the artist – the diptychs created so far are a grappling with her inner processes and states. The source inspires, sets an example, prompts creation. The artist responds, draws from herself, gives birth. She creates likenesses of her interior, a pictorial meditation with a very strong, feminine self reference.

Obsessively, ecstatically, the works are created one after the other: weiß (white), Plateau (plateau), Schlund (gorge), XXX (2017), opposing (2018), in die Tiefe (in the deep), Fichten (firs), Schauer (shower), weiße Ebene (white plane), Hochland (highland) (2019), Wehen (pangs), energie (energy), Offenbarung (enlightenment), komplementär (complentary) (2020) and Ponge (2021). This is not a series: Each diptych stands alone and was started afresh, allowing colours and thematic approaches to carry on from one work to the next. The sketching and accentuation of the conifers and mountain vary. Each diptych is a carefully thought-out construction with emphases of design and content reflected in part and yet openly in the selected individual titles. The intense flesh tones so familiar from Elbequell, a translation of the area’s blossoming heather, are put to use once more in the works from 2017 and reach their dramatic zenith in Schlund. Plunging fantasies of creation and destruction, life and death are worked out here – for the flowing, ever-renewing is confronted by the potentially ominous, the uncontrollable. In 2019, a vivid blue gains significance. It is put to use in multiple diptychs until white and red once again take command. In weiße Ebene, the source, the energy centre, suddenly seems to have retreated into the distance – from a lofty point, the viewer looks down on a lonely, covered expanse. This work reveals the greatest freedom and emptiness of all diptychs so far. Hochland features a cyclical return of the red that, as carmine and orange-red, in energie vigorously breaks fresh ground out of the blue. A great, extroverted liberation takes place here, one also made picturesquely visible in large sections removed with turpentine. In opposing and komplentär, Kießling fathoms oppositions of drawing, painting and colour.

In regarding the as-yet incomplete series, one notices the artist freeing both her content and technique from the given undercoat (which also varies, as the utilised prints-by-chance are not all alike). The mountain peak and fir trees may continually reappear as anchor points, yet the scenery’s planes and the use of painterly tools are treated freely. Whereas the lithograph still came through strongly in early works and the artist worked more intensely with drawing, colouration, building up, in later pieces oil applied with brushes is joined by oil via pen, the colour application becomes more gestural, pastose and partially trowelled. Kießling begins zu wash off points of colour with a turpentine-soaked rag, scratches colour off the paper with a scalpel, becomes ever more expressive. In her diptychs, she fundamentally uses the means of colour and form to run through universally valid moods, inner conditions and shapes, that which is elementary to the human interior.

Yvette Kießling has discovered her personal site of power, her source of creative inspiration – within herself. With her diptychs of the Elbe’s meadow, she gives us viewers the chance to partake and find ourselves in it.

Anna Wesle

Verdichtungen

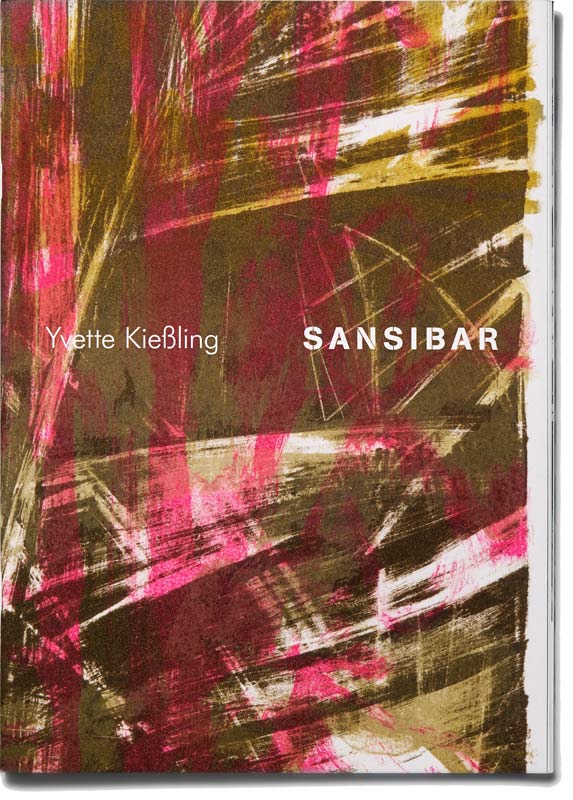

Yvette Kießlings Sujet ist die Landschaft, die sie am liebsten direkt vor Ort malt und zeichnet. Um sich einer Landschaft malerisch annähern zu können, muss die Künstlerin zunächst ein Teil dessen werden, was sie schließlich zu einem Gemälde verdichten wird. Ihr Blick wird dabei von allen Sinnen genährt, und topographische Besonderheiten werden unmittelbar physisch erfahrbar, wenn sie ihr Mal- und Zeichenmaterial in unwegsame Regionen trägt oder sogar 30 kg schwere Lithosteine auf wackeligen Booten bearbeitet. War es zunächst die Auseinandersetzung mit der heimischen Landschaft um Leipzig oder dem Riesengebirge und dem Verlauf der Elbe, so malte sie in den letzten Jahren auch wiederholt in Nordafrika und in Vietnam. Ein befreundetes Sammlerpaar lädt Yvette Kießling 2016 nach Sansibar ein. Fasziniert vom Licht und den Farben und Formen der Natur sowie vom Reichtum der Ornamente in dem ostafrikanischen Inselstaat, rüstet sie sich zwei Jahre später mit einer Feldstaffelei, Leinwänden, Papier und Zinkplatten aus, um auch in Sansibar vor Ort arbeiten zu können. Der riesige „Urwald“ Jozani Forest im Zentrum der Insel zieht sie besonders in ihren Bann. Er erweist sich als verwilderter Mahagoni-Kulturwald, den einst die englischen Kolonialherren an gepflanzt hatten. Sich selbst und dem tropischen Klima überlassen, erscheint er heute exotisch wild, mit üppiger Fauna und Flora und eigener Affenart. Die Künstlerin malt und zeichnet vor Ort, und sie ritzt, sticht und schraffiert in die mitgebrachten Zinkplatten.Sieben dieser Motive lässt sie später in Leipzig als Radierungen drucken, die dieser Mappe beiliegen. Fünf ihrer Zeichnungen aus dem Jozani Forest überträgt sie bei dem Leipziger Steindrucker Thomas Franke auf Lithosteine; ineinander verwobene Mangroven und blühende indische Mandelbäume, darunter auch ein Bildnis ihres täglich gemalten männlichen Modells, der dem Betrachter stolz frontal gegenüber tritt. Im Hauptberuf Barkeeper ihres Hotels, wird der Mann im Bild zu einer würdevoll archaischen Figur. Um das Überbordende,Undurchdringliche und visuell kaum Erfassbare des verwilderten Waldes zu zeigen, revolutioniert sie ihre Drucktechnik. Sie lässt nicht nur ein Motiv von einem Lithostein drucken, sondern zumeist mehrere der fünf Motive in immer anderen Farb- und Formvarianten übereinandersetzen. Beim Trocknen jeder Schicht entscheidet sie über die nächste Auswahl an zu druckenden Steinen und die jeweiligen Farben. In bis zu acht Druckgängen verdichtet sich dabei der Blick in den Wald bis ins Undurchdringliche. So entstehen 100 Unikat-Drucke in immer neuen, ungesehenen Kompositionen. Fünf Variationen davon stellt sie für jede Mappe zusammen.Ergänzt werden die Radierungen und Lithographien von einer abstrakten Toncollage auf CD, für die sie Fledermauspfeifen, Vogelgezwitscher, sich aneinander reibende Bäume, Stimmen und allerlei andere Geräusche der Insel zusammenmontiert hat. Mit dieser außergewöhnlichen Kombination gelingt Yvette Kießling eine ganz besondere künstlerische Verdichtung ihrer Sinneseindrücke Sansibars.

Dirk Dobke

Untameable Vision – Deep Fathoming – Catching Hold of the Open

One way of gaining access to Yvette Kießling’s work is to ponder the untameable. With her pieces, she continually tackles boisterous surroundings, including those made by human hands – not to restrain nature, to tame it, to tidy it. Her open-air works are no pictorial appropriations, no retroactive imposition of order. Rather, they open paths into the thicket.

Yvette Kießling’s work follows the shift from indoors to outdoors, into the open air and into the studio. With this interchanging movement, she always returns to a concrete piece of the world – when that return is denied, the longing for it remains. Apart from painterly idylls, the plein air is Yvette Kießling’s necessary and ultimately natural way of working. Her location hunts have a created a personal map of creation spots.

Neither programme nor creed guide this dynamic, which rather feeds on the tension between location-specific impression and creative elaboration, reshaping, further working. These translate into the choice of representational techniques and means – etching and sketching, oil on canvas on wood, multi-coloured ink lithography, over-painting in oil on Alu-dibond. The flexible switch between media that arises from her working process becomes her mode of artistic adaptation.

Yvette Kießling’s painting and graphic work is an open endeavour – which also explains her return to locations familiar from previous pictures, her recurring viewing. She reaches no closure, partially because the landscape, heavens, plants and ocean and river and mountain are themselves in flux and Yvette Kießling, in her ongoing works, must incessantly experience and see them anew and differently. Her works confront us not with landscape portraits, but with engagement with the idiosyncrasy of a place in the world: tropical growth in Zanzibar or Thailand; the Elbe’s source, scarce in vegetation; the North Sea’s vast land and great sky. On location, the perspective and framing are neither intentionally haphazard nor intricately calculated – they ensue, become harmonious with each image. Yvette Kießling’s works are often drenched in colour, freeing themselves from local lighting moods and encountered colourings. Their opulence speaks of exuberant growth, of virulence and abundance.

The traditions underpinning this creation have deep roots, though such references are not Kießling’s concern. We find, perhaps, echoes of Jacob van Ruisdael, of Caspar David Friedrich, of William Turner and Henri Rousseau. Yet inspiration is ultimately inaccessible, it arises neither solely from the outside nor from the inside. It is expressed, one could say, when Yvette Kießling is confronted by situations and begins to paint. It lies within the synergy between that which she encounters, her wilfulness and the artistic tools at her disposal: intuition and inspiration as interplay.

When she works in series, she does not aim at the replication of motifs. Yet each individual piece initiates pictorial patterns that themselves trigger new permutations. It is pictorial thinking and seeing further, methodical and reflective. Piece after piece, often in series, deals with the complete grasping hold of form traits and colour structures. The focal points of sceneries vary, yet the pictures are never done with them. They are continually new approaches that, placed side by side, never form a mirror of the place in question. Each unicum flows into the next – the ungovernable grows into the work.

Christian Pentzold

Zanzibar

Barred Paths: The Tropical Zanzibar Cycle by Yvette Kießling

Yvette Kießling is a painter. In the past ten years, however, she has also intensively dedicated herself to the artistic possibilities of the graphic arts. This parallel work process and her immersion from the one medium into the other have produced astonishing interplays, which in the past years have become particularly visible in her pictorial sequence of river courses and most recently the Zanzibar cycle of 2017-2018.

Kießling’s work is characterized by the fact that she partially positions herself in a pictorial tradition that developed between 1850 and 1900. Around 1900, artists, including those of the Expressionist movement, re-discovered techniques of carving, scratching and etching, to great success, and ushered in a renewed, deepened artistic relationship with nature, which the Impressionists had previously discovered with their plein-air paintings. Wassily Kandinsky especially juxtaposed colored lithography with its spontaneous style and colorfulness to the lino- or woodcut, as a technique that he claimed lay closest to both pastose painting and direct sketching. Yet the artist is also anchored in the present, as she also exposes the post-modern artificiality of her pictorial ideas. Her current Zanzibar project can serve as a good example: In it, she discovers a new pictorial language in order to connect an immediate experience of nature with a calculated pictorial process.

Yvette Kießling is continually driven to paint across from and within nature. She stands, swims or sits in the midst of her subject. While she pursues a specific topic or motif, her artistic executions are in no way subject to any system or plan. The environment determines the rhythm. One gains the impression that she switches the dynamic during the painting process: Her brushstrokes whip through the image like rough lashes that halt midway, followed by precisely utilised, featherlike and radial bundles of lines defining a leaf, plant or tree.

Her open system of diverse painterly structures follows the subject in front of her. Something that at first shows itself as an unordered mélange of dark, heavier earth and green, shimmering plants and trees that sway in the wind and light under a barely visible sky. Like an explorer, the painter uses her paintbrush to draw a path on the canvas through diagonal plants, upstretched branches and roots and builds up a stimulating tension between the thicket of the tropical nature and light-colored swathes, the long beams cutting through the twilight.

Graphic works form the starting point of these paintings. The Jozani Forest, a natural rainforest of mangrove trees, palms and ferns that has been preserved on the island of Zanzibar, inspired Yvette Kießling to execute a graphic project that developed over the course of her two stays in Zanzibar. Etchings are followed by early colored lithographs. The graphic cycle Zanzibar, comprising 100 unique prints, developed in 2018; it serves, she explains, as a motif pool for artistic possibilities for her painting.

The creation of a leaf – first spontaneously through ink and brush, then slowly and in stages in the lithographic process – does not gain its unusual dynamic until the printing process. By printing up to five motifs in different colors over each other, the artist interweaves them to a degree that does justice to her “rainforest” subject, in an almost ironic way. For the core of the tropical world – which in East Africa is considered the cradle of humanity – has begun to crumble. The jungle with its so-called noble savages had ceased to exist even in Gauguin’s times. Zanzibar, too, can no longer be experienced as an untouched paradise or interpreted à la Walden. The tropics have made way to a protected park landscape of cultural-historical construction, bringing with it the scoriae of their multilayered past – the myths, the peoples travelling through, the colonial powers, immigration and, last but not least, radical encroachments upon the environment.

By playing through numerous motif combinations in the lithography and thereby repeatedly bringing herself to the limit of artistic possibilities, rendering the danger of chaotic superimposition ever present, she takes up this historically multiple, ambivalent construct of tropical nature.

In her painting, this explicitly anti-classical depiction of nature, which is unwilling to open up for the viewer but rather closes itself to his or her perception, is even more prominent. For the depicted path with its moist mire often appears impassable – plants block the way and the view of the sky is obscured, with brown, green and red forming a lattice-like wall that in some works is no longer optically oriented up or down. The general topic of her Zanzibar works, it becomes clear, is a depiction of nature that pushes back against a liberating, clear view: A vast landscape, thicket, undergrowth looms before the viewer’s gaze, forming a dense yet colouristically strongly differentiated wall comprised of over a dozen shades of green.

The impenetrability of the jungle and the inexhaustibility of its shades of green has fascinated painters such as Maurice de Vlaminck, Henri Rousseau or currently Peter Doig and Anthony Gross, who created a proliferating digital jungle for the London Underground in 2015. The outstretched arms of the vividly colored tropical plants, growing unchecked, contain both the conviction as well as, perhaps, a quiet warning that they will, in the end, outlive the metropolitan jungle of human civilization.

by Viola Weigel

Taken from: Yvette Kießling: Sansibar, dt./eng., Leipzig, 2018

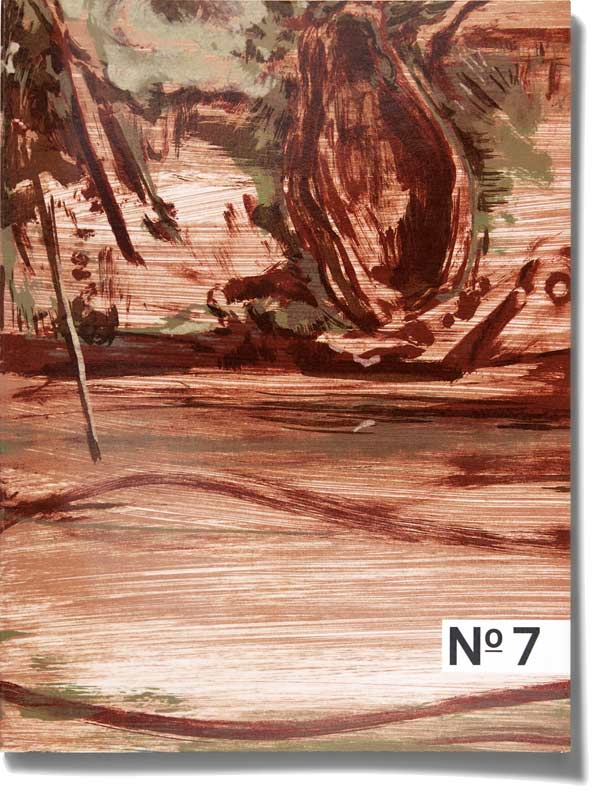

N° 7

Scenic spheres, pictorially captured.

Observations on Yvette Kießling’s painting en plein air in the moors by Bremervörde.

Moors are inhospitable places, their nature particularly untouched—the jungles of the sweeping heaths. They consist of millennia-old plant particles and form landscapes of unmatchable suspense. Such places fascinate the Leipzig painter Yvette Kießling, who seeks out, for her pictures, those landscapes in which she senses a special aura. In her oil paintings, she develops equivalencies for what she experiences in nature. Her aim is to capture the tensions and harmonies she senses in a place and to translate them into her pictorial language.

Over the past years, the painter has discovered her landscapes both along European streams — especially the Elbe and the Rhine — and in far-flung areas like the tropical regions of the Usambara Mountains in Tanzania. After extended stays in such places, the moorlands around Lower Saxony’s Bremervörde now make up her newest area of study. Unlike the thick, noisy tropical landscapes, the moors, with their quiet expanses, appear downright hostile. Their great age and the “dense energy” she perceives lend them a special appeal.

Yvette Kießling paints en plein air: face to face with nature, never mind the wind or weather. All works presented in this catalogue were created under open skies. For the impression of a landscape that interests the painter is so multifaceted that it cannot be adequately captured in photographic or similar reproductions. These impressions transcend the visual appearance and include both knowledge about the site — here particularly the millennia-old history of the plants condensing in the peat — and the lived experience — the daylight and its transformations—as well as her own constitution and inner state at the moment of her natural encounter. Of course, no picture can directly capture either the cold that creeps below one’s clothes on a rainy autumn day, or the cranes that descend in flocks upon the moor, commanding attention from time to time with their loud calls — but these are all aspects of the painter’s impression of the landscape that she seeks to express in her paintings. Yvette Kießling is uninterested in reproducing a scenic situation as she visually perceives it. She is not fixated on documenting each individual element’s concrete number and location, or its specific hue. Rather, she translates what she sees in the manner in which the image demands. The painter compares the process of translating the discovered scenic sphere into the pictorial medium to freestyle musical improvisation. With an ingenious system of revisionary colour applications, she develops her images successively. Her particular handling of oil paints allows her to capture the process of experience: After laying out the image’s structure, she adds its pieces—the plants, clouds, sky, shadow surfaces etc.— step by step, yet always permits herself to remove them again, scratching them out or wiping them off with turpentine. In this continual process of creating and taking away, Yvette Kießling subjects herself to the landscape and presses onwards until she recognises her impression of the site in the picture.

Part of her experimentally playful painting process is her treatment of an imprimatura, a colourful background increasingly found in Yvette Kießling’s pictures. Responding to these at times vibrant and loud shades (magenta, orange, violet or ultramarine) poses a particular challenge in the painting process. The initially selected musical backdrop —to stick with our image of musical improvisation — can be described as the developing painting’s tone. In selecting the prepared, colourfully composed pictorial medium, the artist relies on her spontaneous judgment while regarding the landscape and mood of the day. It is this fearlessness and spontaneity in Kießling’s painting — expressed also in her colour choices, quick strokes and strong interest in the oil paint’s substance — that produces the strong dynamic inherent to her paintings. Her rapid painting method is reflected in various open structures. The pictures often peter out towards their fronts or sides, leaving the backdrop visible on the edges and condensing the image towards its centre. This creates the exciting compositions and unique dynamic that characterise Kießling’s pictorial interpretations of landscapes. The painter developed the intense vibrancy of her pictures during her residencies in Tanzania, where capturing the lush tropical vegetation called for strong colours. She has since retained her willingness to wield strong hues, and now increasingly applies them to those pictures she bases on European landscapes as well. On Bremervörde’s moors, she has thus created paintings that are fascinating expressions of the quiet of the wide moorlands, with its air of loneliness and calm, in startling tones and unexpected dynamic energy.

Yvette Kießling often returns to the places that she has already explored through painting once before. In the past years, this has produced an array of scenic spaces that serve as the objects of her visual world: the Elbe’s source and estuary, the Usambara Mountains. Hopefully, the moor, too, will play a lasting role in the painter’s oeuvre and develop into a site of long-term artistic examination — one from which paintings may emerge that lend onlookers a new understanding of this extraordinary natural sphere.

Benjamin Dörr (Berlin)

Dr. Benjamin Dörr is an art researcher and art historian, a lecturer at the Fachhochschule Potsdam and a freelance publicist. He wrote his dissertation on the middleclass garden art of the Biedermeier era. By empathising with places that used to be parks but are frequently nothing more than overgrown, wild natural environments today, he feels a kinship with the painter Yvette Kießling’s methodology.

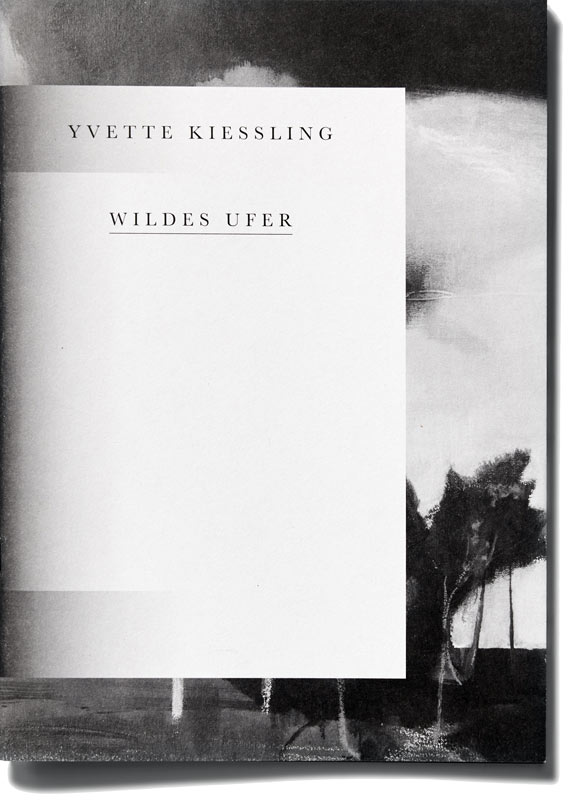

It starts with fuzziness. The colour spots and splashes evidence a kind of fumbling on the canvas and prepare a paradox, which we experience in the pictures of Yvette Kiessling at the end.This paradox gives the special quality to each and every of Yvette’s pictures and it derives from the way of her painting. The process of painting is primarily being nourished by the tense attention in pouring of the paint and the experience of drawing in the countryside or in front of the model. Yvette, on one hand, uses paint as material and rejects any imitation and she stresses its visual intensity. On the other, she uses the paint to colour the objects and create representational islands in her pictures. Human beings, animals and vegetation appear with hazy background. The synthesis takes always place in her studio. The realistic (similar) meets the non-realistic (not similar). Though this, a remarkable experience happens to the viewer of the picture. Instead of detaching, like the classical landscape pictures behind the „window“ of the frames do, the eye of the viewer come closer and is touched and confused. The material of the paint move into foreground and let the viewer dream of invisible pictures, independently from what it depicts at the moment. Yvette’s pictures always aim at presence instead of representation. The viewer takes the helm, opens the play of associations and finds himself in the middle of the wild embankment.

Matthias Weischer, 2012

Cabinet pieces

Yvette Kiessling surprises in her small landscape painting through individual handwriting and her preference of small formats (the size of most of her works is just 16 x 20cm). Her motifs are as old as the earth: clouds, the sea, the mountains, a glacier, a forest, a river. In the history of the landscape painting those archetypes of nature were loaded with pathos. In her pictures however, there is only a far reverberation of it to be felt. The embankments, trees or rivers offer no romantic, or heroic sights. Sometimes a factory chimney or a warehouse show. A waterfall turns into a blue stripe, which stands like an abstract sign in the middle of the picture. Another time a river appears not in blue but in shining white. Those transformations and alienations appear almost unobtrusively.

The picture itself is what the paintress is interested in. For this purpose she gathers the drawings of the landscapes she visits. Her drawings are detailed and topographically precise. In the paintings however, instead of exact enumeration of the details she rather deals with forms and surfaces as a kind of whole. No blades of grass or whole meadows, but spots in green, brown, blue or white determine the earthy effect. The landscape in a state of resting (often in horizontal format) is combined in a tachistic resolution. The heavy and the light are mixed together in cloud formations. The picture of the landscape starts to move from the inside. The paintress expresses the liveliness, which she sees in the landscapes and transfers it into her pictures by means of sketchy brushwork, often using runny colours and arbitrary treatment of light. The traces of the oscillatory movements of the brush remain recognizable. The pictures come into being in her studio so the spontaneous act of painting becomes priority. No more is the landscape is the subject now, but the rise and fall of lines, a rhythm of their movements, relation of colours and light or the interaction of surfaces and depth. The freedom of abstraction in play with realism gives high tension to the pictures and makes them so attractive.

The landscape plays a secondary role in the younger Leipzig painting scene, presently dominated by narrative and abstract painting. All the more remarkable is this artistic position, which handles encounters with nature and the burden of the traditional genre in such subjective and laid-back manner.

Dr. Jan Nicolaisen, Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig